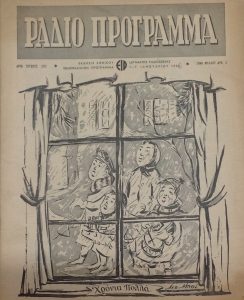

For Greek-speaking radio audiences Christmas programming instantly evokes the work of the celebrated prose writer Alexandros Papadiamantis (1851-1911). In the early 1950s, especially, when the few printed editions of Papadiamantis’ writings were rare to find, radio disseminated his work, introducing it to younger audiences.

His short stories were the ideal fit for a twenty-minute evening broadcast, while the Christmas and Easter setting of a large part of his work made it perfect for season programming. Even today, the film adaptation of his novel The Murderess was released in Greece on 30 November 2023 and became the box-office hit of the holiday season.

Undoubtedly, one of Papadiamantis’ Christmas radio favourites is the short story ‘Love in the snow’ (1896), which I chose to present in this post, in English translation by Janet Coggin and Zissimos Lorentzatos (Athens: Domos Publications, 1993).

Heart of winter. Christmas, New Year, Epiphany.

And the man would get up in the morning, throw his old reefer on his shoulders, the only clothing still left from the years before his prosperity, and go down to the seaside market from the old half derelict house, murmuring so that the woman who lived down his alley would hear him:

― This love is fuel, that’s what it is, not gruel…; this is a lover-boy, not an old boy.

He used to say it so often that the girls of the neighbourhood who heard him finally nick-named him: “Uncle Yanni the lover-boy”.

For he was no longer young, nor handsome, nor had he funds. All these he had used up many years ago, together with the ship, in the sea, in Marseilles.

He had begun his career with this very same reefer when, as a sailor, he first joined his cousin’s brig. He had acquired, from his portion of the profits made from the runs, a part share of the ship, later he bought a ship of his own and made successful runs with it. He had worn English baizes, velvet waistcoats, top hats, had hung watches on chains of gold, had acquired money; but all had been swallowed up in time by the Phrynes* of Marseilles, and nothing remained with him except the old reefer which he wore thrown around his shoulders when he went down in the morning to the quay to ship as partner on a lugger in some small freight business or to go in a borrowed dinghy to catch the odd octopus in the harbour.

He had no one in the world. He was completely alone. He had married, and been widowed, had a child, and been left childless.

And late of an evening, at night, at midnight, after drinking a few glasses in order to forget or to warm himself, he would come back to the old half derelict house, pouring out his pain in songs:

My long, narrow alley, winding downhill to the bay,

Make me, too, a neighbour of the lady down the way.

Other times complaining cheerfully:

My chatterbox and liar, wager of the chin,

Not once did you say, my Yanni boy, come in.

•

Heavy winter, the sky closed for days. Up in the mountains snow, sleet down on the plain. The morning reminded one of the ditty:

It’s raining, raining and it’s snowing,

The priest has got his handmill going.

The priest hadn’t got the handmill going, the woman down the alley, the chatterbox and liar of Uncle Yanni’s song, had it going. Because that’s what she was: the miller’s wife, working by hand, turning the handmill. Note that at that time the local gentry didn’t like to eat bread kneaded with flour from a water mill or windmill but preferred it ground by hand.

And she had a great clientele, this chatterbox. She glistened, she had big eyes, she had paint on her cheeks. She had a husband, four children, and one small donkey to carry the flour. She loved them all, her husband, her children, her little donkey. Only Uncle Yanni she didn’t love.

Who was there to love him? He was left alone in the world.

•

And he had fallen in love with this chatterbox down the alley, to forget his ship, the Laises** of Marseilles, the sea and its waves, his torments, his debaucheries, his wife, his child. And he had taken to the wine to forget the neighbour.

Often, when coming back in the evening, at night, at midnight, his long, tall, lean shadow – with the reefer falling away, slipping from his shoulders – appearing in the long narrow alley, and snowflakes, white flies, wisps of cotton driven to whirlwinds in the air, falling to the earth; seeing the mountain turn white in the darkness, seeing the window of her room shut, mute, the upper window flap shining mistily, dimly; hearing the handmill still squeaking, the handmill stopping, hearing her voice grind, and remembering her husband, her children, her little donkey, all of whom she loved, while she never so much as looked at him – he would feel smoked out like a swarm of bees, stunk out like an octopus, and be given over to philosophical thoughts and poetical images.

― If only love had arrows! … had snares… had fires… With his arrows to pierce the windows… to warm hearts… to set his snares upon the snow… Old man Ferejélis catches thousands of blackbirds in his traps.

He was imagining love as a sort of old man Ferejélis, spending all day out there on the high, pine-shaded hill, busy setting snares in the snow to catch innocent hearts, like half-frozen blackbirds searching in vain for some last windfallen olive left behind in the olive grove. Gone from the wild olive trees the small oval fruits on the mountain of Varadás, gone the blossoms from the aromatic myrtle bushes in Mamoús’s gorge, and now the chattering baby blackbirds with the dark plumage, the sweet blackbirds and the merry thrushes fall victim to the traps of old man Ferejélis.

•

Many an evening, coming back, not too heavy with drink, he would glance at her windows, shrug his shoulders, and murmur:

― One God will judge us… and one death will separate us.

And then with a sigh would add:

― And one graveyard will bring us together.

But before returning home to sleep, he could never help intoning under his breath:

My long, narrow alley, winding downhill to the bay,

Make me, too, a neighbour of the lady down the way.

•

The other evening, the snow had spread a sheet all over the long, narrow alley.

― White sheet… to whiten us all in the eye of God… to whiten our inner core… that we might not have bad feelings inside us.

He dimly fancied an image, a vision, a walking dream. As if the snow were to level and whiten everything, all sins, all the past: the ship, the sea, the top hats, the watches, the chains of gold and the chains of iron, the harlots of Marseilles, the debaucheries, the misery, the wrecks; to cover them, to purify them, to enshroud them, that all of them might not be present naked and laid bare, and as if issuing out of orgies and frankish dances, in the eye of the Judge, the Ancient of Days, the Thrice Holy. To whiten and enshroud the long and narrow alley with its downhill slope and its stench, and the old and crumbling small house, and the filthy and tattered reefer: to enshroud and cover his neighbour, chatterbox and liar, and her handmill, and her suavity, her petty politics, her prattle, her glistering, her paint and varnish, and her smile, and her husband, her children and her little donkey; all, all to be covered, to be whitened, to be purified!

The following evening, the last one, at night, at midnight, he came back more drunk than ever before.

He was no longer able to stand on his feet, no longer able to move or breathe properly.

Hard winter, crumbling house, devastated heart. Solitude, boredom, world weary, bad, pitiless. Ruined health. Body tormented, used up, worn out vitals. He could not live any more, feel, rejoice. He could not find solace, warm himself. In his cups he stood, in his cups he took a step, in his cups he slipped. By now his steps were uncertain on the ground.

He found the way, recognised it. He caught hold of a corner stone. He swayed. He leaned his back against the wall, braced his legs. He murmured:

― If only fires had love!… if only traps had snow…

He was no longer able to form a logical sentence. He was confusing words and meanings.

Again he swayed. He grasped at a door. By mistake he touched the door knocker. The knocker rapped loudly.

― Who is it?

It was the door of his neighbour the chatterbox. One could easily have said that he was trying to go up, rightly or wrongly, into her house. How not to?

Upstairs lights and people were moving about. Perhaps preparations were being made. Christmas, New Year, Epiphany, all close by. Heart of winter.

― Who is it? the voice said again.

The window creaked. Uncle Yanni was directly under the balcony, unseen from above. It’s nothing. The window closed abruptly. Ah, for a moment’s delay!

Uncle Yanni propped himself upright by holding the doorpost. He tried to sing his song, but the words were coming into his submerged mind like shipwrecks:

“My neighbour the chatterbox, long, narrow alley!…”

He barely articulated the words, and they remained almost inaudible. They were lost in the drone of the wind and in the swirl of the snow.

― And I, too, am an alley, he murmured, … a living alley.

His grip loosened. He swayed, stumbled, sagged and fell. He lay on the snow, and his tall frame took up the whole width of the long, narrow street.

He tried once to get up, and then became numb. He found a terrible warmth in the snow.

“Fires had love!… Traps had snow!”

And the window had closed just a moment before. And if only her husband had delayed for a moment, he would have seen the man fall on the snow.

But he didn’t see him, neither he nor anyone else. And on the snow fell snow. And the snow piled up, heaped up four hands high, formed a peak. And the snow became a sheet, a shroud.

And Uncle Yanni became all white, and slept under the snow, in order not to appear naked and laid bare, he and his life and his deeds, before the Judge, the Ancient of Days, the Thrice Holy.

* Phryne, a famous courtesan of ancient Greece.

** Lais, another famous courtesan of ancient Greece.