When did wireless communication technologies, radio in particular, start invading the imagination of Greek writers? As I noted in a previous post, Greece lacked a national broadcasting network until 1938, when Radio Athens was established under Metaxas’ dictatorial regime. Did this delay prevent Greek writers from expressing visions and anxieties around emergent sound technologies? Let us recall that as early as 1913 F. T. Marinetti described his free forms of expression as ‘wireless imagination’ (‘immaginazione senza fill’).

While these questions await researchers, here I shall discuss an early token of the relationship between radio broadcasting and Greek literature: Manolis Alexiou’s free-verse poem ‘Ultrashort waves (49.83M)’ (1938), which I came across in Alexandros Argyriou’s seminal anthology of modernist poets of the interwar era (1979). ‘Born in 1907 in Piraeus and died in 1963 in Athens. He [i. e. Alexiou] served as Director of the Auxiliary Fund of Personnel of Petrochemical Companies’. Argyriou also informs us that Alexiou published two collections of poems (1935 and 1960), and that his first free-verse poems appeared in the journal Neohellenika Grammata (Modern Greek Letters) in 1937.

‘Ultrashort waves (49.83M)’ featured in Neohellenika Grammata on 12 March 1938 – just a few days before the official launch of Radio Athens on 25 March 1938. Yet, as its title suggests, the poem captures the experience of radio broadcasting on the short waves, that is, broadcasting over long distances and across national borders:

‘Ultrashort waves (49.83M)’

I tuned into all stations.

With my head down for hours, I was struggling

to feel just one beat

of humanity’s heart.

Such silent agony weighed heavily on me

that I was holding its pulse, you might say,

through this switch button made of bone.

Yet I wasn’t able to tune into

the ‘cheerful music’ of Warsaw

the ‘light music’ of Hamburg

and the gypsy music of Budapest.

My hand became weary

passing through the universe

and my open palm in vain

was begging for some warm melody.

God, I wasn’t able to hear

but a muffled clamour and a thud

of countless heavy boots.

Only a stream of voices sometimes

None of which seemed human, though.

A twelve-thousand-watt station

was stubbornly ruining all my ‘receptions’.

But suddenly I was able to hear

as though emerging from the earth’s farthest station

a distant explosion approaching

followed by a thin and weak little voice,

a baby’s cry in the middle of the night.

How enormously intense was the wave

and that station was lying in me!… *

In the opening lines, the narrator’s struggle to receive a clear radio signal is described as a struggle to feel the pulse and heartbeat of humanity. This parallelism evokes early visions of the radio as a medium that would ‘unite all mankind’. In his ‘Radio of the Future’ (1921/1927), for instance, the Russian futurist poet Velimir Khlebnikov envisages a Radio that ‘will forge continuous links in the universal soul and mold mankind into a single entity’. A few lines later, the failed attempts to tune into the broadcasts of Warsaw, Hamburg and Budapest further remind the reader that the poem is set at a time when international radio was still the only choice for listeners based in Greece.

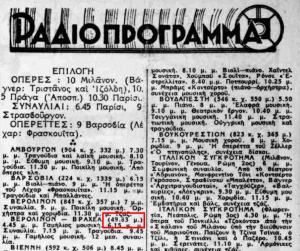

As radio historian Giorgos Hatzidakis has shown, despite the absence of a national network, Greece exhibited ‘a thriving radio landscape’ in the 1930s (2015, 26), even if the latter was limited to transnational listening. The short-lived guide Radiò (1933-1934) wonderfully captures the spirit of this period, for its pages are filled with information regarding the programmes of major European stations. Alongside the daily schedules, Radiò printed additional material related to the European stations in question, such as photographs of radio announcers from various countries or music sheets of signature tunes from different stations.

In the second part of the poem, the ‘silent agony’ (5) prevailing thus far finally breaks. Instead of a ‘warm melody’, however, emerges ‘a muffled clamour and a thud / of countless heavy boots’ (17-18). Which is that powerful station that transmits sounds of boots and inhuman voices, blocking the sound of music? An answer may be suggested by the date of the poem’s composition: 1938, one year before the outbreak of the war. The reference to the ‘distant explosion approaching’ (25) perhaps points to this critical historical moment. Of course, for those who read the poem back in 1938, the answer was more readily available: according to the daily newspaper Ethnos (12.3.1938), the 49,83m wavelength, which features in the poem’s title, corresponds to Radio Berlin.

By 1938, Radio Berlin shortwave station not only functioned as a chief vehicle of Nazi propaganda but also served as a model for the shortwave stations of other countries, such as fascist Italy. In the end, the poem under discussion thematizes the transition from the ‘wireless internationalism’ (Potter 2020) of the early 1930s to the radio propaganda and ‘wireless nationalism’ of the final years of the 1930s.

•

* The translation of the poem into English is mine. I would like to thank Semele Assinder and Ned Allen, who helped me improve my translation.

REFERENCES

ALEXIOU, M., ‘Ultrashort waves (49,83M)’ [‘Υπερβραχέα (49,83Μ)’], Neohellenika Grammata 67 (1938), p.5. The issue is available online. Accessed 6.3.2024.

ARGYRIOU, A. (ed.), Greek Poetry: Modernist Poets of the Interwar Period [Η ελληνική ποίηση. Νεωτερικοί ποιητές του Μεσοπολέμου], Athens, 1979.

HATZIDAKIS, G. O Holy Ether… History of Greek Broadcasting [Ω, άγιε αιθέρα… Ιστορία της ελληνικής ραδιοφωνίας], Athens, 2015.

KHLEBNIKOV, V., ‘Radio of the Future’ (1921/27) in The King of Time: Selected Writings of the Russian Futurian, trans. Paul Schmidt, ed. Charlotte Douglas, Cambridge, MA, 1985, p. 155-159.

MARINETTI, F. T., ‘Destruction of Syntax – Wireless imagination – Words in Freedom’ (1913) in Modernism: An Anthology, ed. Lawrence Rainey, Malden, MA and Oxford, 2005, p. 27-34.

POTTER, S. J. 2020. Wireless Internationalism and Distant Listening: Britain, Propaganda, and the Invention of Global Radio, 1920-1939, Oxford, 2020.